In August 2018, I gave a presentation to my project’s funding agency (the US Department of Energy) arguing that we should spend a million dollars to charter a private plane to carry the world’s largest digital camera from California to Chile. In May 2024, I sat in the cockpit of that very plane as we took off from the San Francisco airport, heading to Santiago.

My main argument was that chartering the whole aircraft gives you a lot more control over the shipment. There are several additional reasons why it’s a good idea, but I don’t feel the need to convince anyone here because clearly they already let me do it.

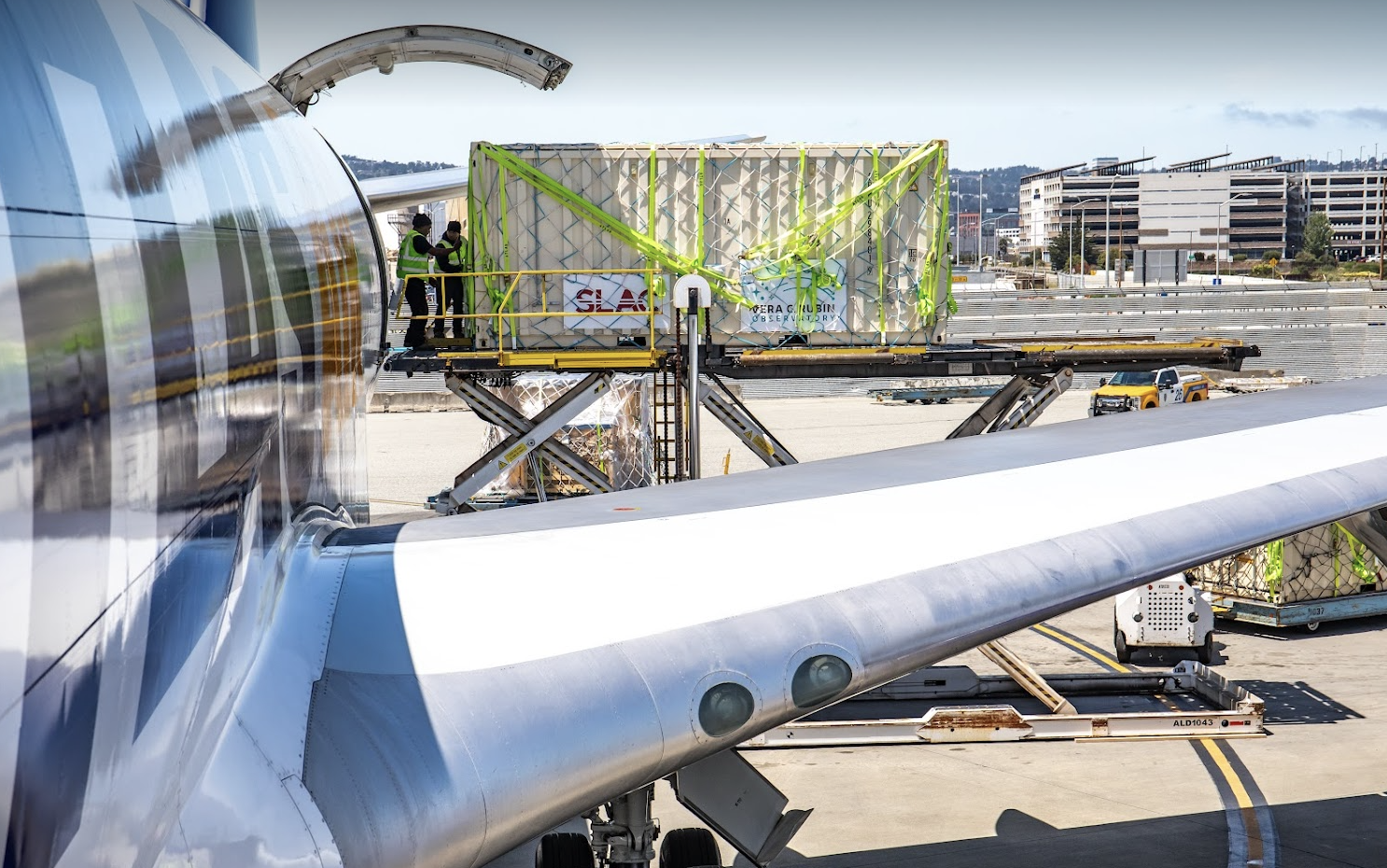

The LSST Camera was constructed in California at SLAC National Lab and had to be sent down to the mountaintop in Chile where it will spend the rest of its days. And of course, once you charter the entire plane, you might as well fill it up with support hardware and maintenance tooling. The final count was 50 metric tons of hardware sorted into 3 standard shipping containers and 43 wooden crates/pallets carefully color-coded in a way that was important to me and probably (definitely) no one else.

The flight was scheduled for a Tuesday afternoon. On the day before, we had six trucks arrive at the lab at 6am to load everything except the camera itself. All that stuff had to get to the airport 24 hours before takeoff to be palletized by the airline and processed by security. The palletization process inside the airport is necessary to assemble all of the crates onto airline-compatible “cookie sheets” that interface with the rollers and locking mechanisms in the aircraft cargo bay, and it was absolutely wild. The forklift driver in particular may be the most skilled worker I have ever seen, moving both the forklift and the cargo around incredibly (frighteningly) fast and with centimeter-level precision. That guy is the real hero.

On Tuesday morning, I followed the camera to the airport at 4am going a breezy 45 miles an hour on a deserted highway. The driver only made one wrong turn and bumped (gently) against a curb which I later discovered was the biggest force/acceleration transmitted to the camera during the entire trip at just over 2g. If you’re not a physics person, that’s super low and we’re excited about it.

It was a good thing we arrived early because there were some shenanigans with weighing the final camera pallet, which was 100 pounds over the scale’s 5-ton weight limit. They ultimately had to drive it halfway across the airport (extra-slowly) to find a bigger scale, which for me was a fun hour-long breakfast break in a nearby diner so I wasn’t too sad about it.

The loading of the cargo onto the plane using the built-in roller system was SO COOL but I wasn’t allowed to take any photos or videos inside the plane for liability reasons. So instead I found a cool youtube video for you, which isn’t exactly the same situation because our containers actually did a 90 degree turn inside the plane, but the floor mechanism is pretty similar.

Because there were only three pilots, one plane mechanic, and two project engineers on the flight (myself and a coworker), it was pretty chill. From another pilot (thank you Papadopoulos), I had gotten a tip off that these guys usually don’t mind visitors in the cockpit, so I got the jump on my fellow engineer and asked the pilots if I could sit in the 4th jump seat for takeoff. Listening in on the headset and seeing everything else happening at the airport from three stories up in the cockpit of a 747 freighter was, again, SO COOL. In fact that’s the theme of this post because I’m too lazy to use a thesaurus (see the title of this post as well).

The passenger area was upstairs from the cargo area via a trapdoor, and had a single row of four seats (two per side) behind the cockpit. They were just like regular domestic first-class seats, bigger than an economy seat but nothing particularly special. The luxurious part was the sheer amount of space available. I had enough room to make a snow angel on the ground in front of my seat and so obviously I did. I even laid down and slept there for a bit in a nest of jackets to let my coworker sleep in the single bed behind our seats (an even bigger luxury). In the middle of the night, I also sat in the cockpit chatting to the two pilots that were on duty for about an hour, and listened in to their calls to the air traffic control towers that we passed, and I’m repeating myself here but it was SO COOL. My coworker then sat in the cockpit for landing and got an extra cool video of us arriving in Santiago (thank you Travis).

At the risk of stating the obvious, I think my upcoming international flights are going to be pretty tough after that experience. It’s not often you get to hang out with the pilots, make a snow angel, and nap on a bed for a little bit during a 10+ hour flight. In fact I can confirm that I got to do none of those things in the several international flights that I’ve taken since then.

I will forever be grateful for this experience even though it came at the price of almost never being home for six months. I promised Will that I’d be home more in the second half of the year and that hasn’t quite panned out yet but, for real this time, 2025 will be the year of being in Tahoe.

Spoiler alert, the LSST Camera did eventually make it from Santiago to the Rubin Observatory in Chile, and the story of the Chilean side of the shipment continues here.

August 27, 2024 at 15:05

That is SO COOL! Thanks for sharing this. What an experience!