After a week of frolicking by ourselves, my mom and I joined up with a tour group from the Sierra Club to do the Salkantay trek to Machu Picchu. It’s not the classic Inca trail that people usually talk about, but it’s still an Inca trail. And while the Salkantay trek is less popular, it’s also less crowded and the landscape was absolutely stunning, so I think it’s a worthy alternative. To be fair I haven’t done the classic Inca trail to compare, so clearly I need to go back ASAP. (No complaints here, I already decided that Peru is my new favorite country.)

In this case in particular the Sierra Club (our group) partnered with a tour company in Peru that has some private lodges along the Salkantay trail so you can do an intense and beautiful multi-day hike without sleeping in a tent. And while I don’t mind camping, I am definitely not going to say no to a comfy bed and a hot tub if they’re available. (If you’re ever interested in doing something similar, I wrote up a post with some packing tips specifically for hut-to-hut treks as well.)

I don’t think a play-by-play of the trip would be particularly interesting to write or to read, so I’ll just run through some highlights, but rest assured that the entire experience was incredible. Doing a real trek in the region instead of just taking the train from Cusco to go visit Machu Picchu directly was absolutely worth the time and effort. We experienced a wild range of ecosystems along the way, learned more about the Incas, and really appreciated the destination once we got there.

Group Dynamics

I’ve been on a handful of group trips with one or both of my parents (Santorini, Kilimanjaro, Mont Blanc) and I am now a big believer in the concept. My mom and I are pretty good travel buddies (I might even venture to say great travel buddies) (love you mom) but it’s always nice to have fewer reasons to disagree (someone else made the plan, not me!) and more people to talk to instead of being each other’s only entertainment for two weeks. It’s also more relaxing for everyone in the family when the vast majority of the planning responsibility is taken away and you can just enjoy the trip. Instead of spending a lot of brain space and discussion time on various hiking routes and dinner options, my mom and I just spent more time hanging out with each other and our new friends in a beautiful place.

On this particular trip, the group that we traveled with was amazing. It’s wild that in just a week we went from twelve strangers to a cohesive and supportive and arguably fun group. It helped that four of the women were already friends from childhood, but I think the overall group bonding is still something to be proud of.

I was initially a little worried about being the youngest one there. At the beginning it feels hard to know where I fit in as a thirty-year-old with less than half the life experience of every other person in the group. However, everyone was very open and welcoming and I had a wonderful time sharing stories and laughs and uphill grunts and (mostly solicited) life advice. I think it’s notable that people sat in different places every evening for meals (i.e. not eating with the same person/group all the time) and mingled in different groups on the trail instead of sticking to a specific hiking buddy all the time. We all got along remarkably well, which is definitely a risk when signing up for a group trip.

I was also grateful to be able to use my spanish language skills to chat with the non-english-speaking staff, like the people taking care of the support horse or working in the lodges or carrying extra water for us. For example, one day while hiking I learned that our porter of the day, Victor, had been walking that exact part of the trail carrying water for tour groups for more than 2 decades. His youngest daughter is a beekeeper and the other two daughters work in teaching and tourism, and his only son works in the kitchen at a Mountain Lodges of Peru lodge (i.e. where we were staying) and is studying. He didn’t say exactly what the son is studying but every Peruvian I’ve met thus far either studied civil engineering or to be a trekking/tourism guide, so it’s probably one of those. We also talked about the impact of tourism on the families (mostly good) and what a kula cloth is for (it’s a reusable pee cloth for hiking and it was a bit awkward to explain to a 65-year-old man but I did it). These are the connections that make this trip feel special, the small window into someone else’s life that allows you to understand them for a short moment.

Shaman Ceremony

During one of the days, we were fortunate to be able to participate in a special Quechuan ceremony with a local shaman named Sebastian. The hike of the day took us to Humantay Lake, which Google says is at 13,780 feet of altitude but our guide said it was just over 14,000 ft so I know who I’m inclined to believe. Anyways, once we had arrived and relaxed and taken some photos, we went to a sheltered area where Sebastian started by laying out his materials and handing out colorful hats to all of us as well as three coca leaves representing the sky, the earth, and the water. We stood, holding the leaves to our mouths, and meditated together facing the mountains.

The building of the offering (which Sebastian called the preparation of the “cake”) came next. In turn, we each brought our leaves to the altar, and then he gave us a blessing to ask the mountains to ensure us a good trip. The coca leaves were piled in the center of a wool cloth, and then covered by many more objects that Sebastian carefully arranged, including seeds and grains, candies, animal crackers (I’m not kidding), metal balls representing the planets, metal strings for trails, flowers, and colorful confetti. He then tied it all up with a pink string and a rock bow, to be brought back to the lodge for the final part of the ceremony.

Just before dinner, we sat in a circle around the fire pit, and Sebastian cleansed each of us one by one. We then meditated in a circle while the shaman burned the offering, followed by hugs all around to complete the ceremony. I don’t consider myself a particularly religious or spiritual person, but I appreciated the care and thought that went into each part the offering, and the time to meditate and reflect, and the shared love for nature. If there’s one thing we can all agree on, the mountains are special and should be respected and protected as such.

Inca Architecture

We were introduced to some examples of Inca architecture early on in the trip, and while it’s hard to see in the photos, the precision of the carving and placement and size of the stones in person is truly astonishing. The Incas created amazing walls and paths and buildings and drainage systems and monuments, including stones weighing over 100 tons and carved to perfection, and are often compared to the ancient Egyptians in their ingenuity. Plus they did it all without draft animals, iron tools, or wheels.

I proceeded to spend a perhaps outsized portion of the trek imagining various ways to move car-sized stones with the simplest of tools and even my most creative ideas are far from adequate. Moving a giant stone on a zipline of braided fibers or leather feels sketchy. Rolling stones on logs is fine until you have to go up or down and I definitely wouldn’t want to be the one behind the stone pushing it uphill. We saw some evidence of ramps and there was some attempt at an explanation by the guide but I don’t really get how they were actually used because gravity still exists and moving heavy things uphill is still hard. Unfortunately, I feel like asking to see a re-creation with all one thousand people pulling a giant stone up a hill with fiber and leather ropes is too big an ask. And beyond that, the precision with which they carved each stone is absolutely wild. Plus, they made internal locking mechanisms within the walls to brace the most important structures for earthquakes, which National Geographic entertainingly calls “dancing stones”.

Based on the sheer intelligence and problem-solving skills of the Inca people it’s almost understandable why the Spanish invaders were scared of them, but I also didn’t realize the extent to which the conquistadors essentially rewrote the history of the Incas. It’s incredibly sad how much information and cultural wisdom was lost, but I suppose every indigenous culture has a similar story.

Quechua Language and Culture

The Quechua people are the Indigenous people of South America and nowadays, most Quechua speakers are native to Peru. Our local guide, for example, was half Quechua and half Spanish.

I like the fact that words in Quechua are written differently depending upon where you are because it was originally only a spoken language. The name of the town of Cusco/Cuzco/Qusqu/Qusqo is the perfect example. The Andy in me doesn’t like multiple spellings for the same word, but it’s understandably hard to write down a word using an inadequate (latin) alphabet that can’t quite capture all the sounds used to pronounce various words.

Quechuan words are also used for more than one thing at once. At one point on the trek, we stopped at a place called “Llactapata”, which means “resting houses” and “high location” in Quechua. There were many llactapatas built by Incas in the Andes, but only this one was actually named “Llactapata,” which is only a little bit confusing.

Also, I didn’t know before this trip that the Quechuan pronunciation of Machu Picchu is “Machu Peak-chu,” with an extra hard “k” sound in the middle, hence the double “c.”

My last anecdote on the cultural side is the story of the fish. When the Spanish arrived in the town of Cusco, ~250 miles from the coast, they were originally welcomed as visitors by the Incas. Our guide told us a story that in order to impress (or perhaps intimidate) their visitors, the Incas immediately sent a message to the coast using their system of trails and relay-runners (no horses) and had fresh fish delivered and prepared for their visitors the next evening for dinner. We were told that while the Spanish enjoyed their meal, they were very intimidated by this show of power and the connectedness of the Inca empire.

Ecosystems

The nature on this trek was wild. As it should be, I suppose. Our route took us through several types of ecosystems—Polylepis Forest, Puna, Cloud Forest, Rain Forest, and High Jungle—where we glimpsed flowers, orchids, birds, butterflies, mammals (including the wild guinea pig), and more. The Sierra Club trip leader is an avid birder and by the end of the trip he had recorded twenty different species of birds, plus ten different species of hummingbirds (out of the 121 that exist in Peru!).

One of the most special moments on the trip came when I did a bit of extra hiking with the assistant guide. While the rest of the group went down to the lodge for lunch after hiking up to Humantay Lake, we went up to another higher peak, a bit above 15,000 ft. We were hiking through a bowl feature near the peak when suddenly three Andean condors swooped in and started circling around us and the surrounding peaks, coming as close as 30 ft at one point. It was so close that I could hear the wind in their wings and it really just felt like a magical experience.

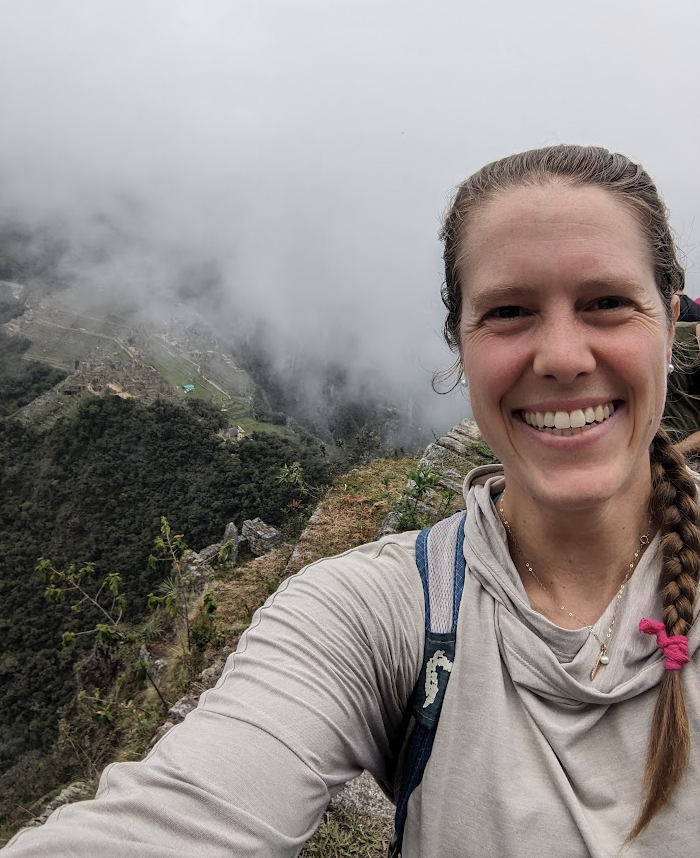

Machu Picchu! and Huayna Picchu

The citadel of Machu Picchu sounds pretty cool in theory, but it really is incredible to see it in person. And because it’s so popular nowadays, you would actually need two days and four separate tickets to see the entire thing.

We spent a whole day touring around the site, filled with fun facts and contemplation and a strenuous hike up to the peak of Huayna Picchu right next door. For example, we learned that the construction of Machu Picchu starts 300 ft underneath for drainage and such, which is why it was preserved so well compared to some of the other sites we toured on the trip. In fact, it is estimated that 60 percent of the construction done at Machu Picchu was underground.

From our guide, we heard stories of Inca kings and priests, astrologers, workers carrying boulders, the extended timeline of the project, and the exploration and hypotheses about why Machu Picchu was built. After learning more about the Inca people, Machu Picchu feels both more impressive and like more of a mystery. Why did they carry stone over from the next mountain to build the site? Was it a royal estate, a sanctuary, a religious center, an astronomical observatory, an administrative center, or something else? Why was such an amazing place abandoned in an incomplete state after nearly 100 years of work?

I can see why it’s a wonder of the world, both in the awe it produces and the mystery that shrouds its past. And after visiting, I can only really say that it’s worth the effort if you ever have the chance to go.

February 19, 2025 at 09:42

This was very exciting & insightful to read. If this was the overview, I could only imagine what an in depth article would look like. I see a book in your future! Immagine a book signing tour!

February 19, 2025 at 12:15

Hi Margaux,

Absolutely amazing trek! So glad you were able to hike through the Cordillera de las Andes. The pictures are stunning, and it looked like a great experience with your mom. Thank you so much for sharing, I live vicariously through your blog posts from South America!

Sincerely

Scott

February 19, 2025 at 13:26

Thanks Scott! Don’t worry, I have a whole bunch more coming :)

February 22, 2025 at 22:28

Margaux! Fantastic! Thanks for sharing these. I always enjoy reading about your adventures. So nice you traveled with your mom.

February 24, 2025 at 20:07

Thanks Neal! I appreciate the support :)